Chlorine radicals (Cl·) profoundly affect atmospheric oxidation capacity. Chloramines, especially trichloramine (NCl3), are emerging precursors of Cl·. However, their sources and roles in the atmosphere remain elusive. Recently, a research team led by Professor Jiang Jingkun from the School of Environment at Tsinghua University, in collaboration with multiple domestic and international institutions, has elucidated the sources, sinks, and transformation processes of atmospheric chloramines. By integrating atmospheric observations, machine learning, and box model simulations, the study quantifies the significant contribution of chloramines to the generation of atmospheric chlorine radicals.

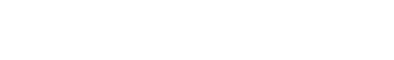

The team first confirmed the ubiquitous presence of chloramines in the atmosphere through field observations. By establishing a calibration method tailored for Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry (CIMS), the researchers conducted quantitative assessments in Beijing, China, and Delhi, India. Significant concentrations of atmospheric chloramines, reaching several hundred parts per trillion (ppt), were consistently observed in both megacities. Analysis revealed two distinct temporal patterns: primary emissions and secondary atmospheric formation. Notably, secondary formation occurred with a frequency of approximately 91%, far exceeding primary emissions and suggesting that secondary processes are a dominant global phenomenon.

Figure 1. Characteristics of primary emissions and secondary formation of atmospheric NCl3 in Beijing during summer: (A) Average diurnal variation of observed vs. simulated NCl3; (B) Time series of a primary emission-dominated scenario; (C) Time series of a secondary formation-dominated scenario; (D) Concentration distribution of NCl3 under different wind speeds and directions.

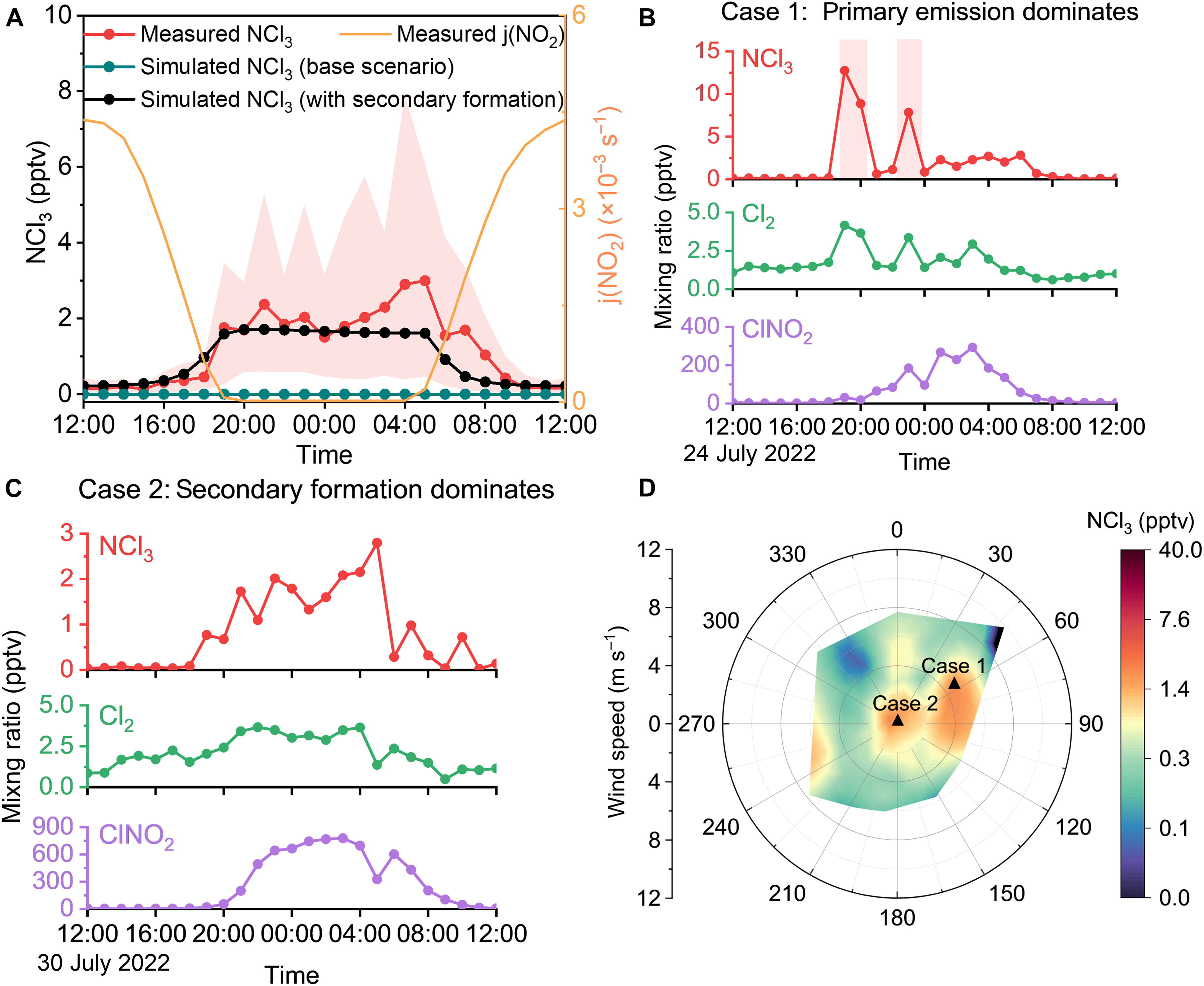

Utilizing comprehensive data from Beijing and machine learning algorithms, the team identified relative humidity and molecular chlorine (Cl2) concentrations as key drivers of chloramine formation. The study reveals that liquid-phase processes involving Cl2 drive the generation of chloramines, leading to the hypothesis that the stepwise chlorination of ammonia in aerosol liquid water is the primary source.

When incorporated into a box model, this mechanism successfully reproduced approximately 64% of the diurnal variation in atmospheric NCl3. Controlled experiments using Cl2 and acidic ammonium sulfate particles further validated this new mechanism. The findings indicate that higher aerosol acidity (pH 4 to 5) promotes NCl3 formation, explaining why concentrations are typically higher on clean summer days compared to polluted winter days.

This multiphase chemical mechanism fills a “missing link” in the atmospheric chlorine cycle. While primary chloramines contribute directly to chlorine radical production, secondary chloramines act as vital intermediates in the conversion of Cl2 to radicals. Simulation results suggest that accounting for chloramine multiphase chemistry increases the global generation rate of chlorine radicals by approximately 10% to 400%.

Furthermore, the relative contribution of chloramines is negatively correlated with PM2.5 levels, indicating that as air pollution control measures progress, chloramines will play an increasingly prominent role in chlorine radical generation. The study suggests that incorporating these mechanisms into air quality and climate models is essential for accurately assessing the impact of atmospheric chlorine chemistry on global environmental change.

Figure 2. (A) Schematic of atmospheric chloramine sources and transformations; (B) Relationship between the contribution of chloramines to chlorine radicals and PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing and Delhi; (C) Impact of chloramine multiphase chemical mechanisms on the generation rate of atmospheric chlorine radicals worldwide.

The research, titled “Chloramine chemistry as a missing link in atmospheric chlorine cycling,” was published online in Science Advances on October 29.

Chen Yijing, a 2020 doctoral student at the Tsinghua University School of Environment, and Xia Man, an Assistant Professor at Nanjing University, are the co-first authors. Professor Jiang Jingkun serves as the corresponding author. Collaborating institutions include e-Surfing Cloud Co., Ltd., Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Nanjing University, Fudan University, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the University of Gothenburg, the University of Helsinki, and Aerodyne Research, Inc. The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China’s “Atmospheric Haze Chemistry” Excellence Research Group project and the Swedish Research Council.

Paper Link:

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adv4298